What Happens To Your Brain When You Move Your Head?

A lot of you are familiar with my work on the relationship between the neck and concussions. It used to be something of a fringe concept that neck injuries could be related to some of the symptoms of a concussion, but research on the topic has exploded in the last 10 years. It’s not such a secret anymore.

Recently I had a great conversation with a physical therapist with similar research interests named Dr. Eric Jorde. He brought up a really cool paper that I’d never read about the biomechanics of the brain during normal head movements. You can check out the paper in the link here (fair warning: Lots of math involved):

Quantitative Imaging Methods for the Development and Validation of Brain Biomechanics Models

I’ll be honest. I didn’t understand a lot of what the paper discussed because it talked about the techniques they used to image the brain during movement. However, some of the videos they shared in the supplementary materials are stunning and really help us understand why concussions can happen with violent movement of the neck.

Brain Movement and Head Movement

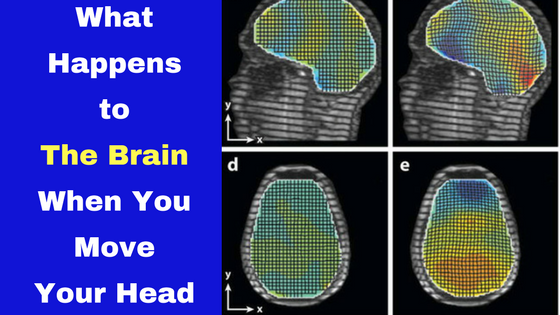

Let’s take a quick look at this gif of the brain on a tagged MRI.

That’s amazing! Look at that grayish stuff covered in a grid pattern. That stuff is the brain inside of a skull as the head turns normally. Does it remind you of anything? It reminds me of a plate of jello when you set it on a table for the first time.

It gives us a good reminder of a couple of concepts.

- The brain really is a soft semi-gelatinous organ that can deform and reform it’s shape pretty easily

- The brain isn’t a static structure. Normal head movement causes very conspicuous movement of your brain even with the surrounding barrier of cerebral spinal fluid.

You can take a look at some videos taken directly from the study at the end of this article.

If the Brain Moves with Normal Head Motion, What Happens When I Really Hit My Head?

So the whole purpose of this study is to get an idea on how the brain may be moving when exposed to head trauma. If just normal movement of the head is creating substantial brain movement, then we can begin to imagine what happens when someone takes a hard blow to the head. Many people associate a concussion with a contusion-type of a trauma….like a bruise.

However, some of the hardest hit parts of the brain from a concussion are not the part of the brain that hit the skull. Many times, the most compromised structures from a concussion are some of the midline parts of the brain like the midbrain and brainstem. This is because that soft gelatinous tissue will experience a SHEAR type of strain from the way the brain moves!

Even forces below the threshold usually required to cause a concussion may be creating excessive movement of the brain and injuring some of the delicate wiring that allows our minds to work. That means that hits to the head, or really rapid head accelerations from things like whiplash may be creating damage to the brain even in the absence of a full blow concussion. Why? Because whiplash injuries are known to create shear forces into the spine, but the brain can also experience some of this as well, but likely at a much smaller amount than a full blown concussion.

Even a force like a whiplash may move the brain enough to cause injury to the brain’s axons

Knowing how the brain moves when the head moves does help to explain why youth and high school athletes can show signs of brain changes in a season of football even without a concussion [1,2]. It can also help explain why some NFL players can have a degenerative brain disease like CTE even if they had no history of a reported concussion.

This is also the reason why that helmets probably aren’t enough to make contact sports safe for athletes long term. You can stop the head from hitting the ground with a helmet, but you can’t stop the brain from sloshing around and deforming when the helmet gets hit.

Conclusion

We can’t fully prevent head injuries from happening to people, but the more that we know about how the brain moves when you move, the more we can do to help make sports and life safer for everyone.

Tagged MRI of rotation

Tagged MRI of flexion

Magnetic Resonance Elastography

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!